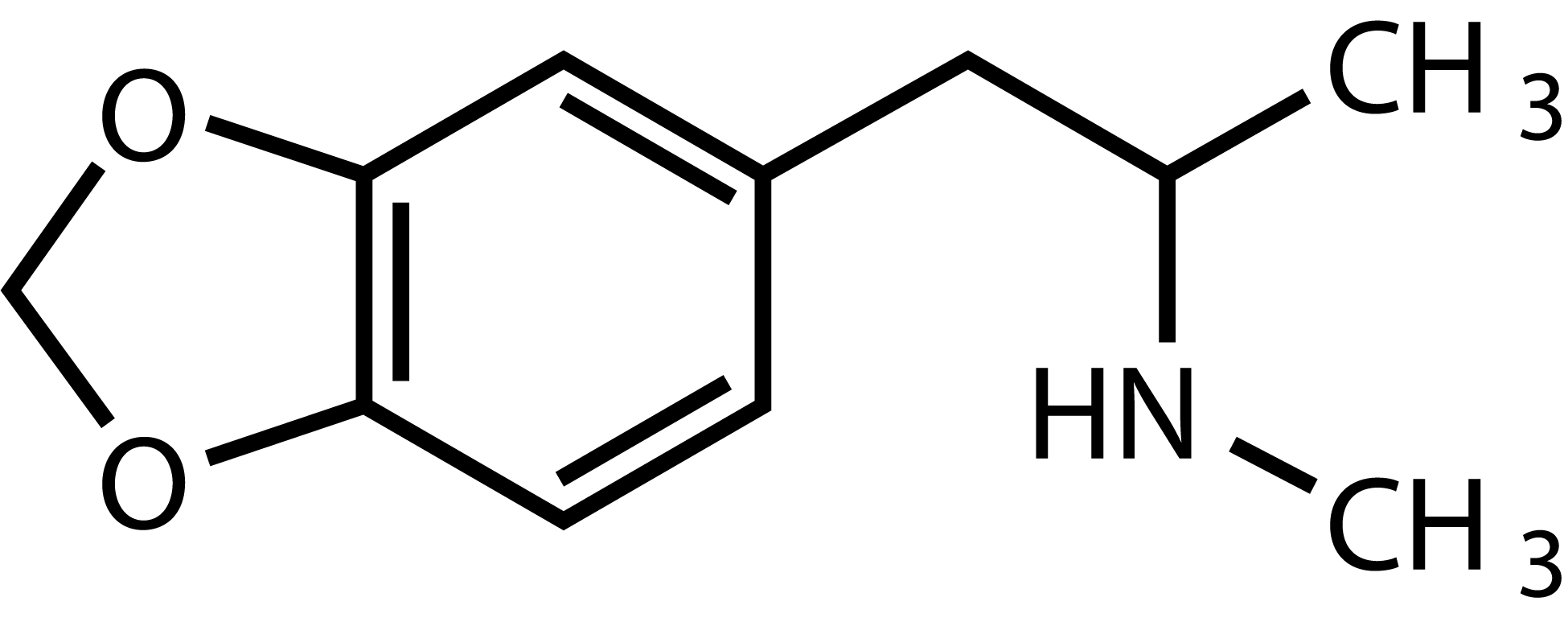

MDMA

ACTIVE DOSAGE (ORAL)

60-150 mg.

DURATION OF EFFECTS

4 to 6 hours on average.

3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine or MDMA is a synthetic amphetamine derivative. Although it is often seen as a psychedelic because of the way it is used in clinical research (in combination with psychotherapy, for indications similar to those of psychedelics), strictly speaking it is not one. It is generally referred to as an empathogen and/or an entactogen because of its particular effects. In addition to altering sensations and its stimulating qualities (common for amphetamines) it promotes physical contact and socialization.

The sought-after psychological effects of MDMA include feelings of increased energy, pleasure, emotional warmth, greater sociability or extraversion and distorted sensory and time perception [1] [2]. These positive mood states are typically observed at low doses of MDMA. At high doses, MDMA may also induce other psychological effects including hyperactivity, agitation, anxiety, depersonalization and mild hallucinations [3] [4].

As with all psychostimulants, MDMA can cause pupil dilation, increased heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature [1] [2] [5] [6]. Other adverse effects including headache, nausea, dry mouth, jaw clenching, increased muscle tension and stiffness and pain in the back and limbs [3]. For a few days following use, some people may show loss of appetite, fatigue, depressed feelings and difficulty concentrating [1] [2] [3] [7].

When taken orally, MDMA is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and reaches the brain within half an hour. The elimination half-life of MDMA is approximately seven hours [8] [9] [10].

MDMA enters neurons via carriage by monoamine reuptake transporters. MDMA has a high affinity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) and norepinephrine transporter (NET) and a lower affinity for the dopamine transporter (DAT). Once inside the nerve terminal, MDMA inhibits the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2), which results in a higher concentration of monoamines in the cytoplasm of nerve terminals and induces their release into the synaptic cleft [11].

The effects of MDMA on positive mood are believed to result from increased release of serotonin in the brain as well an indirect activation of 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors [12]. By activating these serotonin receptors, MDMA also appears to induce the secretion of hormones such as oxytocin, vasopressin and cortisol [13]. Oxytocin is the hormone released during hugging, sexual activities, childbirth, breastfeeding, etc… and is thought to facilitate bonding and trust. The effect of MDMA on oxytocin is therefore hypothesized to be, at least partly, responsible for its entactogenic effects [11].

Increased serotonin release can also produce side effects such as hyperthermia (discussed below), while increased norepinephrine release is responsible for the peripheral sympathomimetic side effects of MDMA [14]. Although the abuse potential of MDMA remains uncertain, it may be associated with increased dopamine release [13].

Besides overdose or risky combinations with other substances, the main risks are dehydration, hyponatremia (caused by drinking too much water) and hyperthermia (especially in cases where people, often unknowingly, have an underlying condition known as malignant hyperthermia). Hyperthermia, or the increase in body temperature, is a well-known and potentially life-threatening adverse effect that is caused by the effect of MDMA on the thermoregulatory system in the brain [2] [5] and it is highly dependent on ambient temperature [14] [15] [16].

Other side effects include bruxism (jaw clenching), insomnia, and an increased blood pressure and heart rate. In the days after ingestion, fatigue, insomnia and mild depression and/or irritability are frequently reported Some suggest these effects to be related to the brain’s serotonin depletion, however there is little data supporting this hypothesis. A more likely rationale attributes these effects to the recreational context in which MDMA was used and are more likely caused by users missing sleep, dancing excessively, using other drugs (including alcohol), and going without food — none of which occur in a clinical setting [17].

Of particular note is the potentially dangerous interaction of MDMA with monoamine-oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). These are commonly used as antidepressants and can also be found in ayahuasca. Such an interaction could lead to serotonin syndrome, which can be fatal.

The long-term risks depend on frequency and dosage: there are no adverse effects if the intakes are reasonably dosed, spaced at least several weeks apart, and if the number of times MDMA is ingested is no more than 50 times during one’s lifetime [18]. However, because MDMA is widely used recreationally in festive settings, often without the proper knowledge, its improper use can be harmful and result in various types of brain damage that can lead to a range of cognitive deficits in chronic users. These could be partially reversible in case of later abstinence. Chronic use, again, often together with the use of other substances, may also be associated with anxiety, depression and cognitive impairments [19] [20] [21].

Research results on the addictive properties of MDMA are still unclear. There is a tolerance effect with MDMA when used frequently, without sufficient time in between dosing, and although it does affect some of the same neurotransmitter systems in the brain that are targeted by other addictive drugs, animal studies have shown that it has less potential for addiction than other drugs, such as cocaine [22] [23].

Deaths due to various causes (hyperthermia, dehydration, hyponatremia, internal hemorrhage, serotonin syndrome, etc.) have been reported, and often highly publicized, but in view of the high use of MDMA, it remains one of the least dangerous recreational drugs, as shown in the 2010 study by David Nutt et al [24].

When MDMA was administered to healthy subjects who participated in a substance safety study, in controlled laboratory conditions, it produced predominantly acute positive subjective effects and dose-dependent cardiovascular side effects, without causing serious adverse effects [4].

MDMA was first investigated in clinical studies during the 1970s and was believed to “fortify the therapeutic alliance by inviting self-disclosure and enhancing trust” [25]. A few studies followed that suggested a potential use of MDMA in patients suffering from anxiety [25] [26].

In 1977, Alexander Shulgin introduced the substance to a therapist of his friends, Leo Zeff, who began to promote it in therapeutic settings. It is estimated that Zeff trained nearly 4,000 therapists for its use in psychotherapy, including couples therapy. Given the fate of LSD, which was outlawed from 1966 onwards, therapists who used MDMA did so carefully and avoided publicizing their use of it. However, recreational use took off and attracted the attention of the DEA, which managed to include MDMA in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, temporarily in 1985, and then permanently, despite appeal proceedings, in 1988. The majority of therapists who used it were forced to give it up, others disregarded this and continued to use it illegally, refusing to stop using a substance they considered too valuable and effective for their practice.

When MDMA was placed on the DEA Schedule I list, research towards its therapeutic effects was halted until the mid-1990s [27], when Phase 1 clinical dose-finding studies were carried out in healthy volunteers to assess the safety profile of MDMA [7] [28]. Early human studies showed that MDMA could be particularly useful in patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [29]. This was followed by a first Phase 2 study in patients with PTSD, showing a robust and long-lasting reduction of symptoms [7].

Medical imaging studies have shown that MDMA reduces the activity of the limbic system of the brain, mainly that of the amygdala, related to emotions, especially fear. Presumably, this activity may explain the fact that traumatized subjects, under influence of MDMA, can revisit their traumatic memories without the fear-conditioned reaction that they usually trigger. It is hypothesized that this allows participants to “deprogram” this reaction during the session.

Several Phase 2 studies have now been conducted in patients with severe and treatment-resistant PTSD, again showing improvements in symptoms [30]. The double blind, placebo-controlled trials showed that 54% of the active treatment group participants no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis, as compared to 23% in the control group. This enabled the FDA to grant Breakthrough Therapy status to MDMA as a treatment for PTSD and facilitated the large-scale randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 clinical trial of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD. This Phase 3 clinical trial demonstrated that MDMA-assisted therapy is highly efficacious in individuals with severe PTSD, and that the treatment is safe and well-tolerated, even in those with comorbidities [31].

MDMA-assisted therapy represents a potential breakthrough treatment that merits expedited clinical evaluation. It may also be efficacious for other clinical populations such as people with autism spectrum disorders [32] and with alcohol use disorders [33].

MDMA has been proven to be much more than a party drug that gives a positive mood state. When administered in a single dose, as an adjunct to psychotherapy, MDMA may offer significant benefits to clinical outcomes.

Given that MDMA is not administered daily, but during integrated therapy sessions with one-month intervals, the risk for side effects or abuse appears limited. Nevertheless, interactions with other medications, such as selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and how these medications should be tapered before MDMA-assisted therapy, needs to be studied further [34]. In addition, the exact modalities of psychotherapeutic integration and how these may optimize treatment outcomes will need to be studied further.

In conclusion, it is safe to state that MDMA has emerged as a powerful adjunct to psychotherapy [13].

[1] S. J. Peroutka, H. Newman and H. Harris, “Subjective effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in recreational users,” Neuropsychopharmacology, 1988.

[2] F. X. Vollenweider, A. Gamma, M. Liechti and T. Huber, “Psychological and Cardiovascular Effects and Short-Term Sequelae of MDMA (“Ecstasy”) in MDMA-Naïve Healthy Volunteers,” Neuropsychopharmacology, 1998.

[3] R. S. Cohen, “Subjective reports on the effects of the MDMA (‘ecstasy’) experience in humans,” Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 1995.

[4] P. Vizeli and M. E. Liechti, “Safety pharmacology of acute MDMA,” Journal of Psychopharmacology, 2017.

[5] M. Mas, M. Farré, R. Torre, P. N. Roset, J. Ortuño, J. Segura and J. Camí, “Cardiovascular and neuroendocrine effects and pharmacokinetics of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in humans,” J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 1999.

[6] S. J. Lester, M. Baggott, S. Welm, N. B. Schiller, R. T. Jones, E. Foster and J. Mendelson, “Cardiovascular effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial,” Ann Intern Med, 2000.

[7] M. C. Mithoefer, M. T. Wagner, A. T. Mithoefer, L. Jerome and R. Doblin, “The safety and efficacy of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study,” J Psychopharmacol, 2011.

[8] L. Y. Lin, E. W. DiStefano, D. A. Schmitz, L. Hsu, S. W. Ellis, M. S. Lennard, G. T. Tucker and A. K. Cho, “Oxidation of methamphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine by CYP2D6,” Drug Metabolism and Disposition, 1997.

[9] Y. Ramamoorthy, R. F. Tyndale and E. M. Sellers, “Cytochrome P450 2D6.1 and cytochrome P450 2D6.10 differ in catalytic activity for multiple substrates,” Pharmacogenetics, 2001.

[10] G. T. Tucker, M. S. Lennard, S. W. Ellis, H. F. Woods, A. K. Cho, L. Y. Lin, A. Hiratsuka, D. A. Schmitz and T. Y. Y. Chu, “The demethylenation of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) by debrisoquine hydroxylase (CYP2D6),” Biochemical Pharmacology, 1994 .

[11] L. D. Simmler and M. E. Liechti, “Pharmacology of MDMA- and Amphetamine-Like New Psychoactive Substances,” Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 2018 .

[12] A. Inserra, D. DeGregorio and G. Gobbi, “Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanisms,” Pharmacological Reviews, 2021.

[13] D. DeGregorio, A. Aguilar-Valles, K. H. Preller, B. D. Heifets, M. Hibicke, J. Mitchell and G. Gobbi, “Hallucinogens in Mental Health: Preclinical and Clinical Studies on LSD, Psilocybin, MDMA, and Ketamine,” The Journal of Neuroscience, 2021.

[14] J. R. Docherty and H. A. Alsufyani, “Cardiovascular and temperature adverse actions of stimulants,” British Pharmacological Society, 2021.

[15] R. Ivine, N. Toop, B. Phillis and T. Lewanowitsch, “The acute cardiovascular effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and p-methoxyamphetamine (PMA),” Addiction Biology, 2001.

[16] Y. Chen, H. T. N. Tran, Y. H. Saber and F. S. Hall, “High ambient temperature increases the toxicity and lethality of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and methcathinone,” Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 2020.

[17] B. Sessa, L. Higbed and D. Nutt, “A Review of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-Assisted Psychotherapy,” Front. Psychiatry, 2019.

[18] J. H. Halpern, H. G. Pope, A. R. Sherwood and S. Barry, “Residual neuropsychological effects of illicit,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2004.

[19] J. H. Krystal, L. H. Price, C. Opsahl, G. A. Ricaurte and G. R. Heninger, “Chronic 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) use: effects on mood and neuropsychological function?,” Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 1992.

[20] A. C. Parrott, T. Buchanan, A. B. Scholey, T. Heffernan, J. Ling and J. Rodgers, “Ecstasy/MDMA attributed problems reported by novice, moderate and heavy recreational users,” Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical & Experimental, 2002.

[21] A. C. Parrott, “Human psychobiology of MDMA or ‘Ecstasy’: an overview of 25 years of empirical research,” Hum Psychopharmacol, 2013.

[22] L. Degenhardt, R. Bruno and L. Topp, “Is ecstasy a drug of dependence?,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2010.

[23] S. Schenk, L. Hely, B. Lake, E. Daniela, D. Gittings and D. C. Mash, “MDMA self-administration in rats: acquisition, progressive ratio responding and serotonin transporter binding,” European Journal of Neuroscience, 2007.

[24] D. J. Nutt, L. A. King and L. D. Phillips, “Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis,” Lancet, 2010.

[25] L Grinspoon and J. B. Bakalar, “Can drugs be used to enhance the psychotherapeutic process?,” Am J Psychother, 1986.

[26] G. R. Greer and R. Tolbert, “Subjective Reports of the Effects of MDMA in a Clinical Setting,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 1986.

[27] D. J. Nutt, L. A. King and D. E. Nichols, “Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation,” Nat Rev Neurosci, 2013.

[28] C. S. Grob, R. E. Poland, L. Chang and T. Ernst, “Psychobiologic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in humans: methodological considerations and preliminary observations,” Behav Brain Res, 1996.

[29] B. Sessa, “Could MDMA be useful in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder?,” Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry, 2011.

[30] M. C. Mithoefer, A. A. Feduccia, L. Jerome, A. Mithoefer, M. Wagner, Z. Walsh, S. Hamilton, B. Yazar-Klosinski, A. Emerson and R. Doblin, “MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: study design and rationale for phase 3 trials based on pooled analysis of six phase 2 randomized controlled trials,” Psychopharmacology, 2019.

[31] J. M. Mitchell, M. Bogenschutz, A. Lilienstein, C. Harrison, S. Kleiman, K. P.-G. and e. al, “MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study,” Nature Medicine, 2021.

[32] A. L. Danforth, C. S. Grob, C. Struble, A. A. Feduccia, N. Walker, L. Jerome, B. Yazar-Klosinski and A. Emerson, “Reduction in social anxiety after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy with autistic adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study,” Psychopharmacology, 2018.

[33] B. Sessa, “Why MDMA therapy for alcohol use disorder? And why now?,” Neuropharmacology, 2018.

[34] A. A. Feduccia, L. Jerome, M. C. Mithoefer and J. Holland, “Discontinuation of medications classified as reuptake inhibitors affects treatment response of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy,” Psychopharmacology, 2021.

- © Psychedelic Society Belgium NGO - 2022

- Zonnelaan 29,1860 Meise Belgium

- RLP Dutch-speaking Business Court Brussels 0756.985.921